Time for action to increase racial equity and opportunities for low-wage workers

September 8, 2022

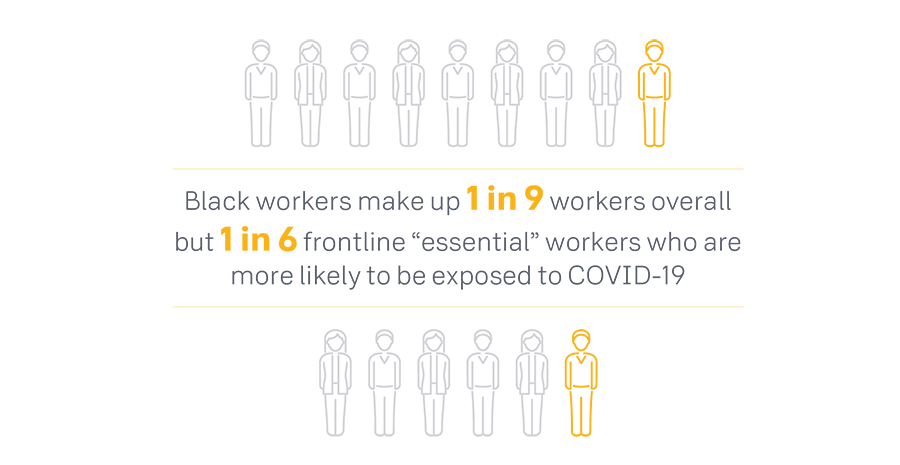

Fundamental shifts in the labor market over the past 25 years have dramatically upended how we work and where we work, with the deepest impact hitting low-wage workers — especially Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) individuals — hardest. The COVID pandemic has only exacerbated disparities for low-wage workers, who experience a lack of benefits, few health and safety protections, and job and income insecurity.

These are among the key findings in our new white paper, Low-Wage Workers Speak Out: The Emerging Future of Work Is Not Improving Their Jobs, which draws upon interviews with more than 30 low-wage workers across Illinois — including caregivers, day laborers, rideshare workers, food production workers, and warehouse workers. What we heard underscored long-standing challenges of race, justice, and equity facing low-wage workers. But the paper also points to new barriers, including significant growth in part-time, gig, or temporary work, and the accelerating use of technology to hire, schedule, and manage workers.

It is imperative that employers and policymakers improve the working conditions, financial stability, and economic mobility of low-income workers, who are primarily workers of color. Diego, a day laborer and one of the workers we interviewed, told us: “Government should do more to ensure that everyone who pays taxes, including immigrants like myself, have access to essential resources and protections on the job.”

As employers have cut costs in the face of uncertainty, more and more workers have been forced into contingent work and the “gig economy,” a structurally racist system of work. Workers are stuck, with no expectation of regaining permanent work. Because contingent workers lack basic benefits and protections afforded most traditional full-time workers — health insurance, paid leave, overtime pay, and minimum wages — they find themselves out on a limb, at risk of exploitation and without protection from harm.

The damage from the new economy, compounded by COVID-19, is particularly painful for Black and Latino/a/x workers, who are more likely to face disruption from work due to automation: 44 and 47 percent of their jobs, respectively, are at risk. Put simply, people of color are overrepresented in the contingent workforce. Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that Black and Latinx workers make up almost 42 percent of workers for Uber, Lyft, and other “electronically mediated work” companies, although they comprise less than 29 percent of the overall U.S. workforce.

With our Future of Work research partners — Alliance of Filipinos for Immigrant Rights and Empowerment (AFIRE); Arise Chicago; Chicago Workers Collaborative; Latino Union of Chicago; The People’s Lobby; and Warehouse Workers for Justice — we uncovered these key concerns among low-income workers across Illinois:

“I’m a single mom of three kids, one of whom has special needs,” Alicia, a nail technician, told us. “I have to take them to school, the doctor, and therapy appointments. My employers have often been unwilling to accommodate my schedule.”

During the ongoing pandemic, we are working hard to ensure that no workers are left behind. Through community collaboration, we have the opportunity to reimagine work in ways that will benefit us all. Our hope is that insights from our interviews with workers lead policymakers both in Illinois and Washington to shape the future of work to increase racial equity and protect low-wage workers from harm.

Our key recommendations include:

More than ever, we need to work toward systemic change that centers the needs of those most vulnerable; low-wage work is a racial justice issue. Join us in working toward laws and policies that will ensure that everyone can have a good job.

Systemic inequities and the legacy of structural racism make it harder for low-income people and people of color to achieve financial stability.

Everyone should be paid decently and have basic workplace protections.