Only by carefully examining all five levels of equity work can we assure that our approach will truly result in liberation.

A commitment to race equity is an integral and essential part of anti-poverty advocacy. But because their work happens across so many levels, it can be difficult for advocates to determine where to start applying a racial justice lens to legal advocacy. Racial Justice Institute Fellow Alice Setrini learned that first-hand in her work managing medical-legal partnerships in Chicago.

In 2015, Alice left the Racial Justice Institute armed with new knowledge and skills to advance race equity in her work at Legal Aid Chicago. As the Supervising Attorney of the Medical-Legal Partnerships Project at Legal Aid Chicago, Alice worked with health care providers, case managers, and social workers to address structural problems at the root of health inequities. Medical-legal partnerships allow patients in healthcare settings an opportunity to meet with lawyers who can help meet needs their doctors cannot. These lawyers can help patients prevent eviction, a lapse in Medicaid coverage, or other setbacks that would impact their stability.

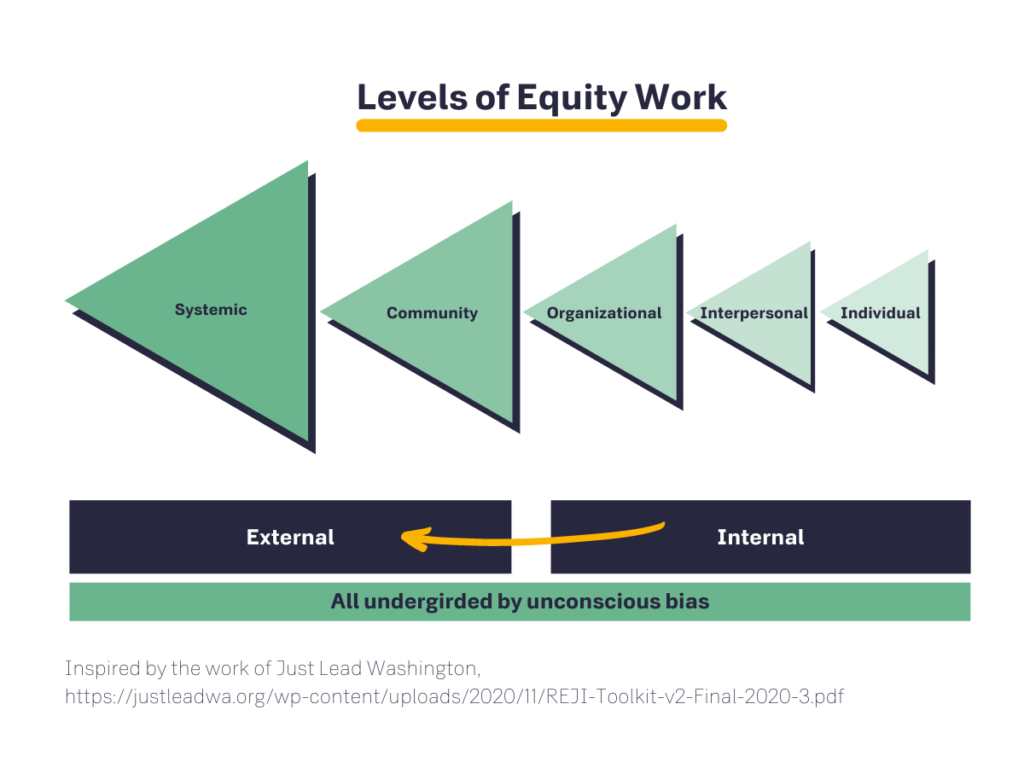

Alice knew that she wanted to apply the tools she learned in RJI to build a more equitable response to her community’s needs, but where to start? Equity work can happen on a continuum of levels, both internally and externally.

Internally, our identities as individuals matter. We have to grapple with where we might have privilege and/or be the target of bias. Where we have privilege, we must determine how to be allies to those who do not. Where we have identities that could make us a target of bias, it is important to understand the broader context of historical oppression and any internalized trauma that could manifest as feelings of racial inferiority.

Because we work with other people, our interpersonal relationships also matter. Everyone involved has to continually consider how they might be contributing to disparate outcomes faced by BIPOC clients. Within our workplaces, it’s important to understand whether our organizational values, culture and vision work to dismantle oppression.

Externally, working within the community, we must assess whether we are focusing resources equitably to help those most in need. And we need to aim our overall work toward disrupting biased systems that we do not control but can influence. Only by carefully examining all five levels of equity work can we assure that our approach will truly result in liberation.

For Alice and her colleagues at Legal Aid Chicago, the need to address the internal and external simultaneously was apparent. Internally, they examined hiring and retention policies to ensure that staff better reflected the diversity of their local community. They initially focused on training staff in the basics of structural racism and implicit bias. Operationalizing what they learned, they began mitigating bias by inserting filters, such as inclusive decision-making within the hiring process, to disrupt the unconscious bias that lies beneath the surface of so many of policies, practices, and cultural norms. “That really shapes what the agency looks like going forward and really centers race equity, not just in the work that we’re doing but in the make-up of the organization itself,” Alice said.

Externally, Alice and her colleagues wanted to ensure that their services were being accessed by communities in the most need. Using their case management system, Alice took part in an audit of clients and communities being served by the organization. Then, using race equity mapping tools, they examined the Cook County, Illinois, region for gaps in communities served by Legal Aid Chicago.

The audit uncovered a disparity in legal aid services to Spanish-speaking preferred clients. “The audit—or the demographic accountability exercise—helped us as an agency examine our practices and look at why the numbers were not what we thought they should be,” Alice said. Initially, Legal Aid Chicago sought to address this disparity by changing the greeting of their automatic phone intake system to “Para español oprima uno” (“If you need this in Spanish, press one”). “With that simple change, the number of Spanish-speaking clients we served immediately increased,” she said.

Using this data, Legal Aid Chicago also made changes in their intake process. By analyzing information about who they were serving, they could also be more mindful about which partnerships to pursue to address gaps in services within underserved communities. Ultimately, Legal Aid Chicago chose to partner with community organizations and health centers whose primary clientele are Spanish-speaking preferred, including a partnership with Erie Family Health Centers.

“The focus of the partnership was to address health harming legal needs for the patients served at Erie, with priority given to legal issues dealing with Medicaid denials/terminations/delay,” said Alice. “Of particular interest to our partners were Medicaid delays for pregnant patients.” Many of these patients were immigrants, and preferred speaking in Spanish and had difficulty navigating the complex public benefits systems.

“Our partner health centers are generally sitting in the communities that we want to serve, so we do programming there,” she continued. “We can meet clients where they live, so it really provides a way to be more present in the community and have better points of service for those folks, creating trusted relationships, enhancing our presence in those areas, and allowing for our organization to better serve the communities that we’re supposed to be serving.”

Legal Aid Chicago’s partnership with Erie Family Health Centers addressed the disparity in services to Spanish-speaking preferred clients; about 50% of the cases that came from Erie were Spanish-speaking preferred patient-clients. It also allowed their work to become more holistic. Because the health centers have strong, trusted relationships with the community members they serve, the medical-legal partnership program was able to expand the range of cases they took on, classifying issues like housing under a broader umbrella of health. “It was really a way to provide a more interdisciplinary and holistic service for our clients,” Alice said.

In May 2020, Alice left Legal Aid Chicago to begin serving as the Executive Director of the Mary and Michael Jaharis Health Law Institute at DePaul University College of Law. She continues to center race equity in her approach in this new position. “Historically, the Health Law Institute focused on issues of law, business, and technology as related to health rather than health equity,” she explained. Now, health equity and racial justice are central to her decisions about programming.

Alice’s experiences at both Legal Aid Chicago and DePaul University College of Law are testaments not only to the impact the Racial Justice Institute has on individual advocates, but also to its impact on entire organizations by ingraining the importance of race equity in their anti-poverty efforts. By making race equity central to the work of its Medical-Legal Partnerships Project, Legal Aid Chicago was able to expand its patient-client base in a way that more accurately reflected the needs and demographics of its community. Moreover, by taking a more community-based, holistic approach, Alice and her colleagues were able to increase access not only to legal services but also housing and immigration services important to that community.

Learn more about the Racial Justice Institute.

This article was written by Janerick Holmes, Associate Director of the Racial Justice Institute. Madeleine Parrish, a former intern from the University of Chicago, contributed to this article.